So far and yet so similar: Convergent evolution in helicopter damselflies

Published:

Sungsik Kong and Emanuel M. Fonseca

This article corresponds to Toussaint E. F. A., S. M. Bybee, R. J. Erickson, and F. L. Condamine. 2019. Forest giants on different evolutionary branches: Ecomorphological convergence in helicopter damselflies. Evolution.doi: 10.1111/evo.13695.

One of the long-standing goals in evolutionary biology is to understand the evolution of alike morphological, ecological, and behavioral characteristics among distantly related non-sister species in response to the exploitation of similar resources. In particular, didecomorphs (i.e., species exhibiting similar phenotype, but not phyletically close) independently evolve their morphology and ecology, or they acquire those characters from a single event? These questions lead to hypotheses that can be examined by interrogating species’ phylogenetic relationships.

Previous studies identified Pseudostigmatidae – a family of ecologically and morphologically similar species – as a monophyletic group composed of 18 Neotropical and one Afrotropic species. However, Toussaint et al. (2019) cast doubt on it because those past studies may possibly be “biased” due to homoplastic morphological characters and/or inadequate sampling. Using a more extensive taxon sampling coupled with morphological and molecular datasets, the authors investigate: (i) whether the Neotropical and Afrotropical species are descent from one ancestral species that distribution broke up when South America and Africa continents moved apart in the Lower Cretaceous (i.e., monophyletic group) or (ii) whether these species share similar morphological and ecological characters due to convergent evolution (i.e., polyphyletic group).

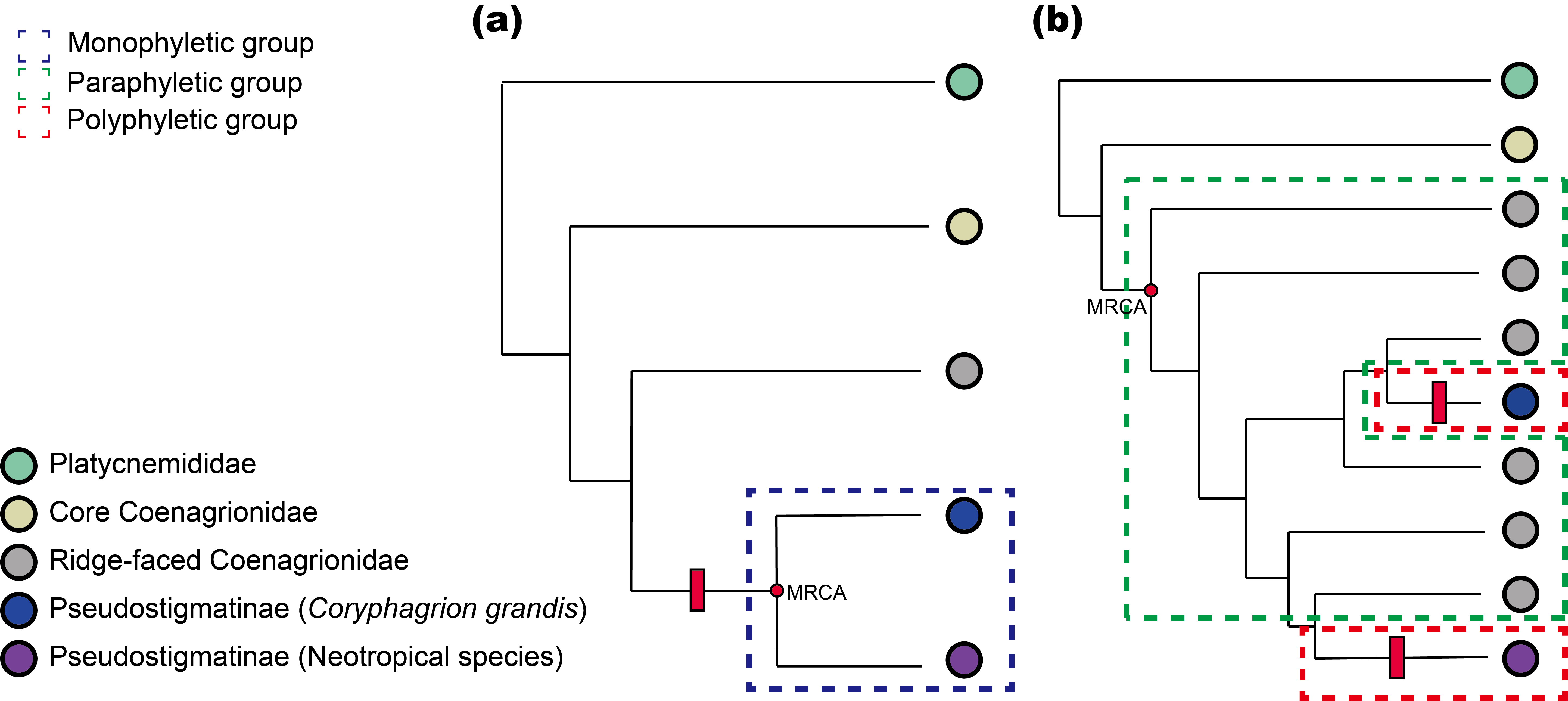

By analyzing ecomorphological data through a Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) phylogenetic approaches, Toussaint et al. (2019) show that the Afrotropical helicopter damselfly Coryphagrion grandis forms a monophyletic group with the Neotropical Pseudostigmatinae (Fig. 1a). However, molecular Bayesian Inference (BI) phylogeny provided strong evidence for convergent evolution (Fig. 1b), which is further supported in the dating analysis. Thus, the authors favor the molecular over the morphological findings and argue that morphological resemblance is consequence of convergent evolution due to similar ecological pressures.

From birds (e.g., Bravo et al. 2014) to cephalopods (e.g., Lindgren et al. 2012), convergent evolution is ubiquitous along the tree of life. This phenomenon is often caused by adaptive evolution leading to the emergence of similar, non-homologous phenotypic traits among species. Convergent evolution sometimes is responsible for the inference of incorrect phylogenetic trees, creating misinterpretation about the processes and mechanisms that have shaped the current biodiversity.

Although such homoplastic characters are not always conspicuous, the use of morphology characters in phylogenetic analyses must not be discounted. Phylogenetic trees inferred from morphological data are thought to be prone to adaptive convergence more than molecular data (Hedges and Sibley, 1994). This argument is often used as reasoning to reject morphological over the molecular-based relationships. But biologists employed morphology to infer evolutionary relationships much longer than the molecular one, and many of them correctly identified taxonomic relationships, and current molecular studies merely reconfirm the groupings, not revise (Wiens et al., 2003).

In short, Toussaint et al. (2019) provide an additional example of how similar ecological pressures can lead to the evolution of similar adaptive traits. Their findings amaze us how two non-sister species occurring in extreme distance can exhibit such ecomorphological similarity. Therefore, because species are exposed to numerous similar biotic and abiotic pressures that influence resource acquisition, convergent evolution is inexorable in natural habitats.

Figure 1. Simplified (a) MP/ML and (b) BI phylogenetic tree inferred in Toussaint et al. (2019). Based on the MP/ML tree, morphological traits evolved once (marked by red rectangle), whereas the BI tree shows that they evolved twice, independently. The MP/ML tree supports monophyly of Pseudostigmatinae, as the group includes the most recent common ancestor (MRCA; red circle) and all descendants. The BI tree does not support such monophyly but identified polyphyly, making Ridge-faced Coenagrionidae a paraphyletic group.

Figure 1. Simplified (a) MP/ML and (b) BI phylogenetic tree inferred in Toussaint et al. (2019). Based on the MP/ML tree, morphological traits evolved once (marked by red rectangle), whereas the BI tree shows that they evolved twice, independently. The MP/ML tree supports monophyly of Pseudostigmatinae, as the group includes the most recent common ancestor (MRCA; red circle) and all descendants. The BI tree does not support such monophyly but identified polyphyly, making Ridge-faced Coenagrionidae a paraphyletic group.

Reference

Bravo, G. A., J. V. Remsen Jr., and R. T. Brumfield. 2014. Adaptive processes drive ecomorphological convergent evolution in ant wrens (Thamnophilidae). Evolution 68:2757–2774.

Hedges, S. B., and C. G. Sibley. 1994. Molecules vs. Morphology in avian evolution: The case of the “pelecaniform” birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9861–9865.

Lindgren, A. R., M. S. Pankey, G. Frederick, F. G. Hochberg, and T. H. Oakley. 2012. A multi-gene phylogeny of Cephalopoda supports convergent morphological evolution in association with multiple habitat shifts in the marine environment. BMC Evol. Biol. 12:129.

Toussaint E. F. A., S. M. Bybee, R. J. Erickson, and F. L.Condamine. 2019. Forest giants on different evolutionary branches: Ecomorphological convergence in helicopter damselflies. Evolution. DOI: 10.1111/evo.13695.

Wiens, J. J., P. T. Chippindale, and D. M. Hillis. 2003. When are phylogenetic analyses misled by convergence? A case study in Texas Cave Salamanders. Syst. Biol. 52:501–514.

Note: See https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13729 for published digest for Toussaint et al. (2019).